Somewhat to my surprise, Orkney looked nothing like the highlands or the Western Isles I have visited. Gone are the barren moors, bens and glens, replaced by gentle rises and sweeping grassland. Cows instead of deer.

One massive exception we saw was the west coast of the Mainland (the main Orkney isle). The sloping grass gives way to sheer cliffs and raging waves. While not as high as the cliffs off Hoy, they are still thrilling and simply teeming with seabird life. Each day on Orkney we would choose a spot by the coast and go for a trek. Across wide, arching beaches, then up headlands and along paths astride the cliffs, holding the kids hands tight.

The coast was full of features I recall from geography at school. Stacks, arches and blowholes. From semi-safe spots, we would sit and pass the binoculars around, spotting birds on cliffs stained white by their excrement, swirling on the wind and perched on the waves. Guillemots, kittiwakes, razorbills, shags, skuas, gannets, you name it. Not to be forgotten were the birds of the low shoreline and backing marshes – oystercatchers, redshanks, turnstones and more. These were great, but what we really wanted to see were puffins…

PATIENCE AND LUCK

Try as we might, we could not sight these evocative little birds. Cliff after cliff showed up many wonderful things, but no puffins. My daughter was equally excited by the semi-tame rabbits on a cliff top, but for the rest of us puffins was the main aim.

Puffins play a special role in British culture, being one of the more extravagant animals left on our dilapidated islands, and featuring in as diverse mediums as book publishers, cartoons and confectionary. I had therefore wanted to see one since I was a kid. It seemed our best opportunity was passing us by, until… on our final afternoon a passer-by on a cliff walk half way down the west coast of the Mainland, tipped us off that they had seen puffins on the Brough of Bursay.

The Brough of Bursay is a small island off the north-west tip of the Mainland, accessible by foot only at low tide. I checked the tide times and, as luck would have it, the tide was going out. I rang the rest of the family and arranged to meet them there asap.

Having transversed the narrow path to the Brough through the rock pools, we passed through the remains of a Viking settlement, over a fence and up a steep hill.

|

| Thanks Uncle Phil |

There was a puffin, and another. So much smaller than I had expected (barely bigger than my hand), but intensely charismatic. A pair were perched on a narrow ledge. One flew off, and as I followed its path, I saw another puffin flying in.

All in all, I think we saw at least 6. We lay there with the kids and cousins, giggling with excitement.

SEALS AND A CREATURE CARCASS

The seabirds were marvellous, but do not hog all the rights to cool wildlife on these isles. Driving around the island, we were fortunate to see seals on multiple occasions. Both grey and harbour seals fish of the coast and lounge around on beaches. The best place we found to spot them was just off the “main” Stromness to Kirkwall road, at the southern edge of the Loch of Stenness. Mildly inquisitive, they would roll over, or pop their heads out the water on seeing us.

Perhaps the most remarkable wildlife we saw was not even alive. Walking by a beach on the west coast, I spotted a large log type shape on the shore that did not look quite right. As we walked closer, I could not work out what it was, until a bad smell and closer inspection gave it away. It was a carcass of small whale. It looked most peculiar and, after doing some research, I found out that it was the mysterious Cuvier’s beaked whale. Living in the deeps of the far north and rarely ever seen, one washed up here was a stark reminder that leave these isles on the wrong heading and all you get is wild ocean for league upon league.

SCUBA SCAPA

Being a keen diver, I wanted to explore Orkney’s waters, as well as its shores, and I was lucky enough to do just that. The simply fantastic Scapa Scuba (who incidentally have the coolest dive shop I have ever seen – a 100 year old bright red lifeboat station), took me to experience my fist ever dry-suit dives on the blockships that guard the eastern approaches to Scapa Flow.

An array of ships were sunk to prevent the Germans from attacking this key Royal Navy base in the two world wars. Sadly, they did not fully do their job, with U47 slipping through in October 1939, and sinking the HMS Royal Oak, with the loss of over 800 hands.

The blockships lie in shallow water between the small islands that run between the Mainland and South Ronaldsay. They have broken up over the years and been enveloped in wildlife. This make an excellent place to dive.

Spotting another seal as we pulled up in the van by a bridge and small inlet, we took our time prepping for the dive. I received great instruction in how to put on the cumbersome dry-suit and what to expect when in the water. We slipped into the shallows, I put my head under and received an immediate ice-cream headache for my sins. The water was all of 7 degrees C and made me grimace. I though got used to it soon enough and opened my eyes to a new world.

Thick sea weed and kelp, giant crabs, fish I had never seen before and huge numbers of starfish. The water clarity was good. I got used to the buoyancy of the dry-suit sooner than expected and followed the bottom as it descended towards great lumps of seaweed strewn metal. It was a thrilling sight.

In all I spent over an hour exploring the wrecks spread over two dives. While heavily broken up, many parts of the structure were still evident. There were great swim-throughs and many a sea creature surprise. A large lobster beneath the wreckage and, strangely most exciting for me, a sizeable cod scared off.

It was a brilliant experience. I got on really well with the dive school guys. They were happy enough with my intro to dry-suit diving for me to join them on the deep dives to what remains of the scuttled Imperial High Seas Fleet (see here), one of the top dive sights in the world. I could hardly contain my excitement. The only problem was weather and a lack of availability. Each day I waited with my fingers crossed. The latter freed up, but not the former. The sea gods were not with me, throwing up prohibitive wind and waves. Yet another reason to return to these wonderful islands.

SINCLAIRS AND SCOTCH

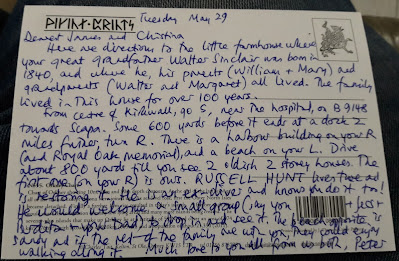

All over the Orkney were reminders of our ancestral link. The name Sinclair is everywhere. What best bought it home though, was finding the small farm house where my great-grandparents lived before departing for Australia. Thanks to my Uncle Peter’s research and careful instructions, we found the place on the eastern side of Scapa bay, round a sharp bend on the Old Scapa Road. After a week on Orkney, it no longer felt strange that my forebears had lived here for centuries, but seeing the house brought with it some sadness for what is gone.

As the mists rolled in, I thought of what a difficult life it must have been through the long, cold, dark winters. We found hints of how they may have survived. Alongside the old pubs, there is more than the Orcadians fair share of alcohol production. Adding to the old whisky distilleries and brewery, are newer gin distilleries. I cannot recommend highly enough Orkney Gin Company’s Old Tom. Never since has our house been without it.

A HIGHLAND GEM

I was genuinely sad to leave. We had had a wonderful time. Adding to all the fantastic sites, adventures and wildlife, was quality time with my family. Seventeen of us had made the mini pilgrimage to Orkney on the beckoning of my Uncle Peter. Without him I am not sure I would have ever have made it, which would have being a crying shame.

On the boat back to Scrabster and the Scottish mainland, we once again passed the intimidating heights of the cliffs of Hoy, simply teeming with wildlife. Alas, we did not see the orcas.

The road back south was a beautiful as before, but our stop over was a bit extra special – Glen Affric. Nestled to the west of Loch Ness, in the middle of the highlands, it is one of the last strongholds of the ancient Caledonian forest, giving it a very different feel to the barren lands elsewhere.

This did not happen by accident. It is a wonderful example of rewilding and the potential it holds. Starting a quarter of a century ago, Trees for Life started installing fencing to keep out deer (who eat the saplings) and then augmented this with planting. Scots Pine have made a comeback. Instead of bare rock and gorse, there are glorious forests (find out more here). We stayed a night by the glen, trekking either side of the dark.

One trek was deep into a dark, mature forest. We spotted pine marten scat (it is sad how excited I was) and came upon a waterfall through the trees. It was magnificent.

The other was into the heart of the glen. We followed paths down through wooded hills, across banks of ragged granite and down to the rushing water.

At a high point, the whole glen opened up before us. It was spectacular. It felt like that so rare thing in the UK, wilderness. I was so glad to be able to take my children to such a place. So glad in fact, that it deserves a montage...

All too soon, we were driving south again and then along Loch Ness to Inverness and our flight home. As the flight took off I took with me a stronger affiliation with the country of both my grandfathers.

No comments:

Post a Comment